Comics have always been a mirror to society’s hidden corners - and sex workers have been there, quietly drawn in the shadows of panels, often as villains, punchlines, or victims. But over the last two decades, a quiet revolution has taken place. Independent artists, many of them former or current sex workers, are rewriting the narrative. They’re drawing themselves not as tropes, but as people: tired, proud, angry, loving, and complex. This isn’t just art. It’s testimony.

Some of the most honest portrayals come from zines and webcomics published outside mainstream publishers. One artist, based in Portland, draws weekly strips about her life as a webcam performer - the late-night shifts, the weird clients, the way her cat sleeps on her keyboard during breaks. These aren’t fantasies. They’re routines. And somewhere in the margins of that story, you might find a reference to sesso a dubai, not as a fantasy destination, but as a reminder that sex work exists everywhere - from quiet apartments to luxury hotels, from online chats to street corners in cities that pretend they don’t see it.

From Sin to Survival: How Comics Changed the Story

For decades, sex workers in comics were either monstrous (think of the femme fatale in noir strips) or tragic (the fallen woman begging for redemption). Even in the 1990s, when indie comics exploded, portrayals rarely came from lived experience. Most artists were men drawing women they didn’t know. The result? A distorted, sexualized version of reality.

Then came the internet. And with it, platforms like Patreon, Gumroad, and Tapas gave sex workers direct access to audiences. No editors. No censorship. Just raw, unfiltered storytelling. Artists like R. O. Blechman and more recently, S. M. Hargrove, began publishing autobiographical comics about survival, stigma, and self-determination. One comic, “The Last Shift”, shows a worker counting her earnings after a 14-hour day - not to seduce, but to pay her kid’s school fees. The panel is silent. Just numbers. A calculator. A half-empty coffee cup. That’s the power of comics: simplicity, honesty, silence louder than any scream.

Real People, Real Drawings

What makes these modern comics different isn’t just the subject - it’s the authenticity. Many artists draw themselves. Not idealized. Not stylized. Real bodies. Stretch marks. Tattoos. Bruises from a bad client. Hair that hasn’t been dyed in months. One artist, who goes by the pen name Wren, posts monthly strips about her work as a natural escort in rural Oregon. She doesn’t glamorize it. She shows the paperwork. The background checks. The way she double-checks every client’s ID. The fear. The boredom. The occasional moment of genuine connection.

These aren’t porn. They’re memoirs in panels. And they’re gaining traction. Libraries in Seattle and Toronto now carry these comics in their social justice collections. University courses on gender and visual culture assign them alongside academic texts. The shift is real: sex work is no longer just a taboo to be feared - it’s a labor issue, a human rights issue, a storytelling issue.

Global Voices, Local Struggles

Comics about sex work aren’t just an American phenomenon. In Brazil, artists draw about street workers facing police violence. In Japan, manga creators depict hostess club workers trapped by debt and social pressure. In India, underground zines show how caste and gender collide in the sex industry. One artist from Mumbai draws her mother’s story - a woman who worked in a brothel after her husband died, then taught herself to read and write at night. The final panel shows her handing a book to her daughter: “This is your weapon,” she says.

And then there’s the strange, quiet mention of siti escort affidabili - not as a search term, but as a footnote in a comic set in Rome. A young woman, new to the city, scrolls through a website on her phone while waiting for a client. The artist doesn’t judge. She just shows the screen: clean fonts, neutral photos, a list of services. No glitter. No promises. Just facts. It’s a moment that says: this is how people find work now. Online. Carefully. Quietly.

The Art of Survival

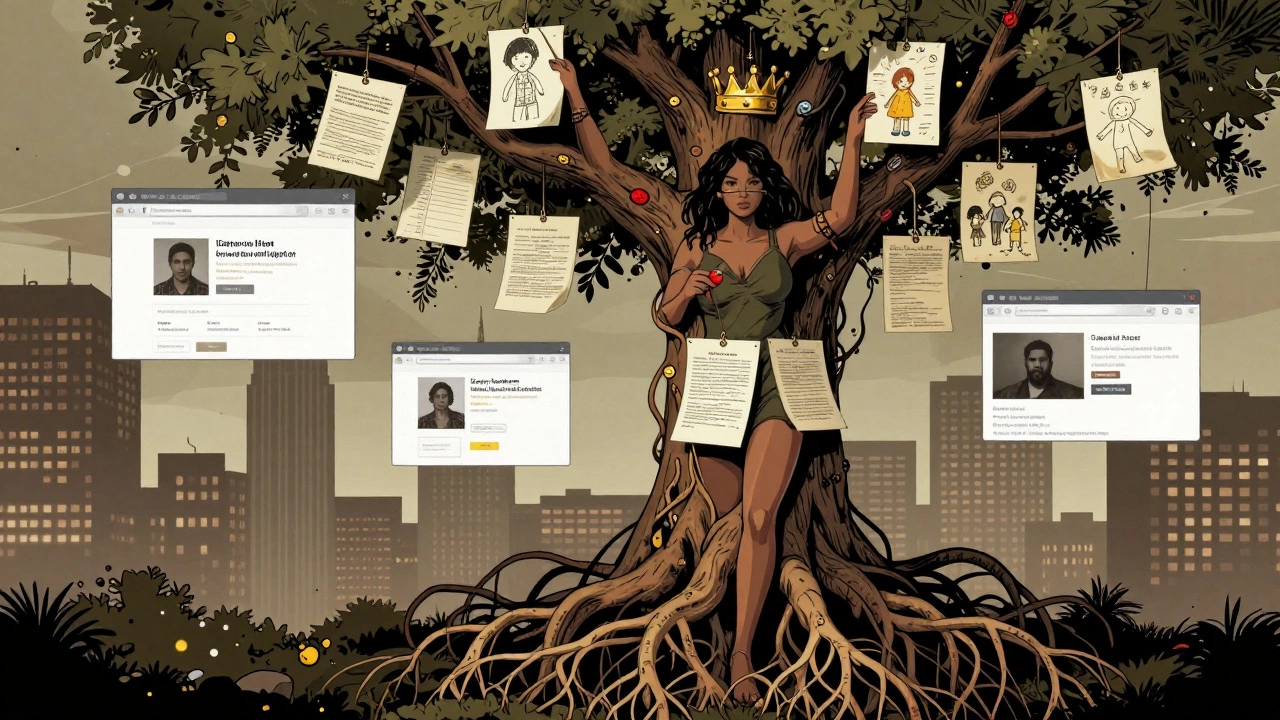

These comics don’t ask for sympathy. They ask for recognition. They show that sex work is not a moral failure - it’s an economic choice, often made under pressure, but still a choice. Artists use visual metaphors to drive this home: a worker wearing a crown made of condoms. A body drawn as a tree, roots tangled in contracts, branches holding children’s drawings. One powerful series, “The Ledger”, uses a ledger book as a recurring motif - each page a transaction, each line a life.

What’s striking is how these artists use color. Not to titillate, but to convey emotion. A panel of a worker lying on a bed after a client leaves might be rendered in cool blues and greys - the exhaustion of solitude. Another, showing her laughing with a friend over tea, bursts into warm yellows and oranges. The contrast isn’t accidental. It’s intentional. It says: there’s joy here too. Not despite the work. Because of it.

Why This Matters

When mainstream media ignores or misrepresents sex workers, comics step in. They don’t need approval. They don’t need funding. They just need a pen, a tablet, and the will to speak. And they’re reaching people who would never read a policy paper or watch a documentary. Teenagers. Teachers. Grandparents. People who thought they knew what sex work was - until they saw a drawing of someone who looks like their neighbor.

Artists aren’t just documenting. They’re organizing. One comic series, “Decriminalize”, ends each chapter with a QR code linking to mutual aid networks. Another includes a checklist: “How to Stay Safe,” drawn in simple icons - a lock, a flashlight, a phone, a friend’s number. These aren’t just stories. They’re survival guides.

What’s Next?

The movement is growing. Comic conventions now have panels on sex work and representation. Publishers are taking pitches from sex worker artists. And more importantly, readers are listening. The next wave might include animated shorts, interactive web comics, or even augmented reality experiences where you walk through a day in the life of a worker - not as a voyeur, but as a witness.

One thing is certain: the era of sex workers being drawn by others is ending. The people who live this life are now the ones holding the pen. And what they’re drawing isn’t fantasy. It’s truth. With all its mess, its pain, its resilience, and its quiet dignity.

And somewhere, in a small apartment in Berlin or a studio in Manila, another artist is opening a blank page. She’s tired. She’s hungry. But she’s ready to draw again. Because someone needs to see this. And someone needs to know they’re not alone.

Write a comment